Background

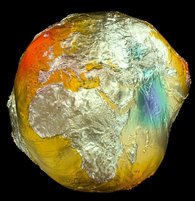

The force of gravity on the Earth's surface varies from point to point. This is because the Earth's body has a more complicated shape than a sphere and the mass density in the Earth's interior is inhomogeneous. Thus, the Earth is oblate due to its rotation, this means the semi-axis of the Earth's body is about 20 km smaller at the poles than at the equator. But even the reference ellipsoid is only a rough approximation of the Earth's shape. The topography of the continents and the bathymetry of the ocean floors deviate by up to several kilometres from the reference ellipsoid. The surface of the oceans, i.e. the reference level of zero metres above sea level, also has bulges and dips of up to 100 m compared to the reference ellipsoid due to differences in gravity caused by density variations in the Earth's mantle. This means that the gravitational field determines the shape of the Earth's body. The 3D image on the left shows, greatly exaggerated, the deviation of the height reference surface from the rotational ellipsoid, known as the geoid. Its shape resembles a potato (“Potsdam potato”). Precise knowledge of the fine structure of the Earth's gravitational field on a global scale is an important prerequisite for understanding the structure and dynamics of the Earth. In addition, gravimetric surveys also allow the investigation of geological structures such as fault zones, faults, salt domes and volcanic formations, as well as ore deposits.

The large-scale structures in the gravity field, ranging from flattening to a spatial resolution of about 80 km, are calculated homogeneously with the help of satellites by precise measurement of orbit perturbations, distance measurements between two satellites and satellite gradiometry. Prominent examples of satellite missions for gravity field determination involving the GFZ are GRACE, GRACE-FO and GOCE.

A higher spatial resolution is achieved by combining satellite data with ground-based gravity measurements and gravity data from ship and aircraft gravimetry and radar altimetry. At the GFZ, global static gravity field models are calculated purely from satellite data, such as GO_CONS_GCF_2_DIR_R6, and combined gravity field models, such as EIGEN-6C4.

To improve the database for combined gravity field models, the GFZ uses two mobile gravimeters on ships and aircraft: a Chekan-AM-type gravimeter from the Russian company CSRI “Elektropribor” and a new type of strapdown gravimeter, the iCORUS, from the German manufacturer ”iMAR Navigation & Control”. The data obtained with these devices are also used for regional gravity field model determinations.

A further increase in the spatial resolution of global static gravity models is possible using so-called forward modelling. We calculate a global gravity model of the Earth's crust using digital terrain models and density data, by numerically integrating Newton's law of gravitation. This gravity model is then combined with satellite and terrestrial gravity models.

Scientific key questions

- How can the spatial resolution of global static gravity field models be increased by combining them with terrestrial gravity data and topography-based forward modelling?

- How can the accuracy of global static gravity field models be improved?

- How do global static gravity field models improve our knowledge of the structure of the Earth?

Related projects