Anatomy of a catastrophe

The tsunami at Christmas 2004

![[Translate to English:] Meeresstrand mit vielen eng gestellten Sonnenschirmen.](/fileadmin/_processed_/7/8/csm_1_AdobeStock_645233151_Foto_afdal_%E2%80%93_stock.adobe.com_klein_c442d0e2b6.jpeg)

Christmas time is one of the peak holiday seasons worldwide. Many people from countries in the northern hemisphere seek warm climates and sandy beaches. Thousands of tourists come each year to the Indonesian islands.

It’s December 26, 2004, in Sumatra, shortly before 8am in the morning, when the rock deep beneath the coast bursts asunder. There were no foreshocks, no tremors, no warnings. The force and extent of the earthquake is unprecedented in Asia’s recorded history.

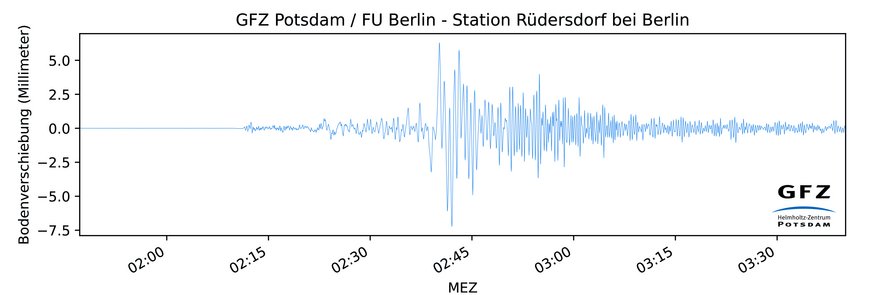

Initial estimates gauged it as a magnitude 8.8 earthquake, later analyses showed that it was even worse: 9.3, the third strongest quake worldwide since earthquakes were recorded systematically.

GFZ’s station in Rüdersdorf, 30 kilometres east of Berlin, measured the wave with local ground movements of more than a centimetre – 10,000 kilometres away from the epicentre the Earth moved 5 millimetres up and 7.5 millimetres down when the wave passed.

This caused a tsunami wave that propagated through the Indian Ocean. Other than normal waves at the top layer of the oceans, tsunami waves affect the whole water column down to the seafloor. A wall of water, several kilometres in height, is pushed towards the shores where, as the sea gets shallower, it spreads like an immense high tide.

The worst destruction happened only ten to fifteen minutes after the initial earthquake when the waves hit the Indonesian coastlines.

The inflowing water reached heights of up to 30 metres.

Sri Lanka, India and Thailand were hit between one and half and two hours later. It took seven to eight hours for the waves to also reach the coasts of Madagascar and Eastern Africa.

The death toll was immense. With few exceptions, people were caught totally unaware in nearly all affected areas.

There had been no tsunami warning system for the Indian Ocean – nor for the Atlantic and nor for the Mediterranean Sea. The only systems in place were for the Pacific Ocean, as Japan specifically had a long and well recorded history of tsunamis spanning centuries.

Sweden and Germany were the two countries with the highest numbers of citizens killed by the “Boxing Day Tsunami” as it was called soon after. The shock in Germany sat deep and the public willingness for help was tremendous.

A tsunami early warning system for the Indian Ocean

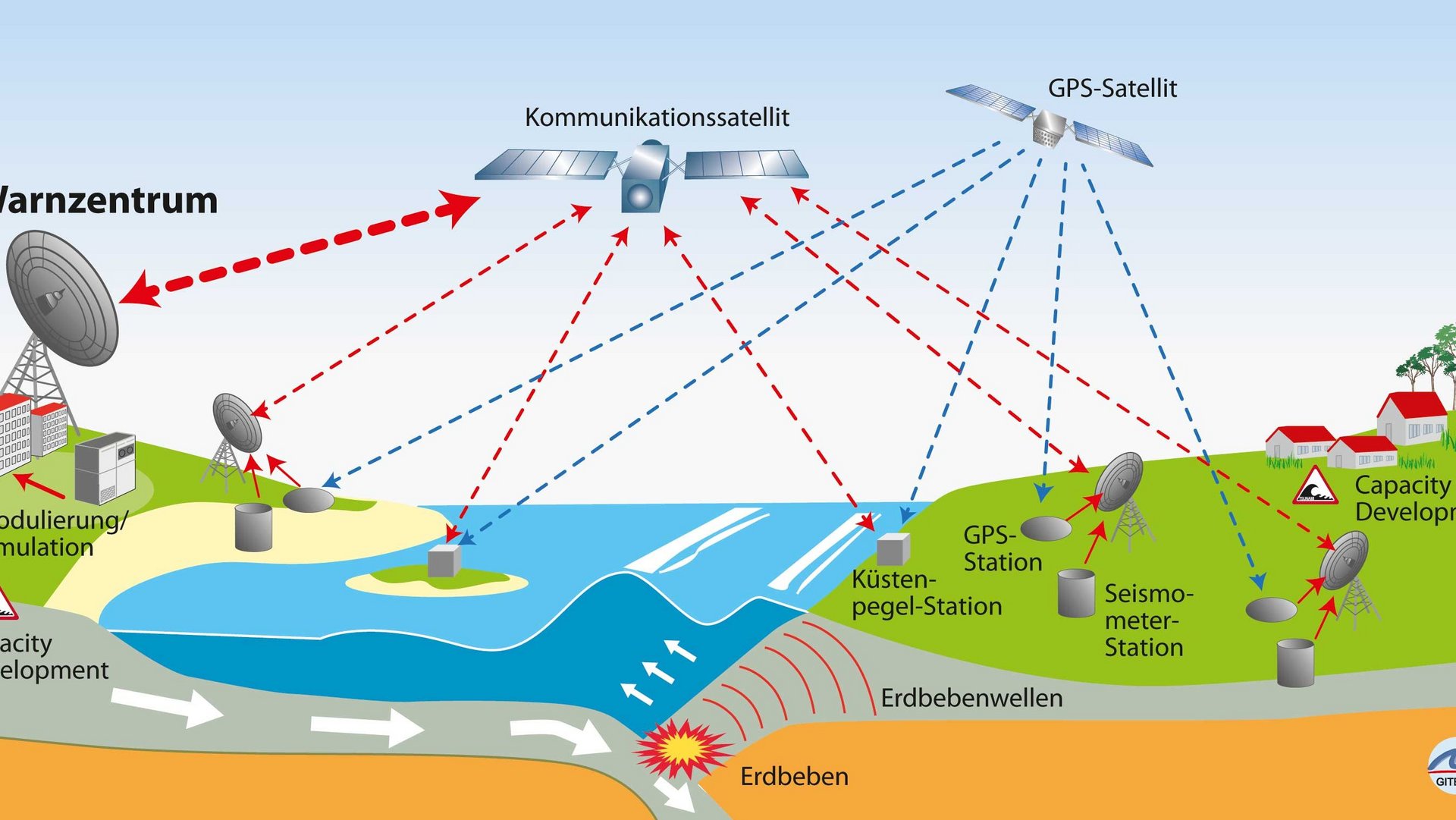

The German government tasked GFZ together with other institutions to develop an early warning system for the Indian Ocean in close cooperation with Indonesia. In March, 2005, the contracts were signed and GFZ led the effort. Several other Helmholtz Centres were also involved: AWI and DLR as well as the GEOMAR which, at that time, was operating under the roof of the Leibniz Association but became a member of the Helmholtz Association in 2012.

One of the core elements of the newly designed German Indonesian Tsunami Early Warning System (GITEWS) was a software developed at GFZ together with colleagues that now have their own company, GEMPA. This Software (SeisComP) is still in use in an updated version and is now widely used. It detects earthquakes and explicitly also those that are likely to trigger a tsunami.

In March 2011, GITEWS was fully transferred to Indonesia and is still in operation, now as InaTEWS (Indonesia Tsunami Early Warning System) under the direction of the Indonesian BMKG (Meteorological Institute, Climatology and Geophysics). InaTEWS system has registered and assessed many thousands of quakes since it was put into operation and successfully warned of a good dozen tsunamis (e.g. Benkulu 2007, North Sumatra 2010 and 2012).

However, it has also reached its limits, especially when the waves reached the coasts only minutes after a triggering quake (example: Mentawei tsunami in 2010, Palu tsunami in 2018). Another notable case was the collapse of a flank of the Krakatau volcano in the Sunda Strait in 2018. This large landslide also triggered a tsunami, but was not detected by the system as there was no strong earthquake associated with the landslide.

![[Translate to English:] Die Vulkane: Batu Tara, Kadovar und Ritter Island haben das größte Potential einen Tsunami auszulösen](/fileadmin/_processed_/e/2/csm_Ranking_Results_Tsunami_risks_by_vulcanos_in_Indonesia_e52500033c.jpeg)

A number of GFZ researchers are still active in Indonesia researching tsunamis as well as volcanoes, for instance Thomas Walter who recently completed the Tsunami Risk Project. Another example is Jörn Lauterjung, who coordinated the GITEWS project for GFZ.

Jörn Lauterjung continued to collaborate with Indonesia and the UNESCO to improve early warning. Even after his retirement in 2020, he is still working as an advisor travelling to Indonesia regularly.

Outlook

Use of existing fibre optic cables as highly sensitive sensors

At GFZ, several projects involving many partners are running, e.g. Geo-INQUIRE, or will begin soon to look further into monitoring the seafloor and working towards integrated early warning systems.

The use of existing underwater telecommunication cables as sensors for monitoring earthquake zones, volcanoes or oceans also opens up great potential for tsunami early warning. The underlying DAS technology (Distributed Acoustic Sensing) uses the optical fibres as strain sensors: movements in the subsurface cause them to deform, distorting the transmitted signals. Information about the movement of the earth can be derived from the analysis and both earthquake waves and processes in the water column above the ground, e.g. tsunamis, can be recorded. This technology is being further developed, for example, in the EU project SUBMERSE (SUBMarine cablEs for ReSearch and Exploration), which was launched in 2023.

Also based on this technology, a major infrastructure project to set up a global monitoring and user centre ‘SMART Cables And Fibre-optic Sensing Amphibious Demonstrator’ (SAFAtor) has been applied for under the leadership of the GFZ and with the participation of other Helmholtz centres, which is scheduled to start in 2025 if approved.